Today marks the last day of the festival week held on the small island where I was raised. In honour of this, I’ll be writing a mini-series on the use of islands as settings and gameplay structures in various games.

Titles that have utilised islands range from cartoon-platformer Crash Bandicoot (1996) through fantastical adventure-JRPG Kingdom Hearts (2002) to action-horror classic Resident Evil 4 (2005). Some games’ settings are comprised entirely of a single island (typically) divided into sub-worlds and levels, with titles such as Yoshi’s Island (1995) unsurprisingly being notable examples. In other games, islands are smaller structures within the overall world, acting as levels, stages or sub-worlds themselves. Islands have also become a recurrent feature in several long-running franchises, including both Zelda and Mario.

Like many elements of game-design, the use of islands within games has borrowed heavily (and often simplistically) from clichés developed in other media. It will come as no surprise then that depictions of islands across numerous games have been somewhat limited in terms of style and aesthetics. Numerous examples fall under the tropical or exotic label, and many others serve merely as ‘evil lairs’. However, there are some functions served by game islands that are likely unique to the medium, and which are facilitated by the needs of traditional game-world structures.

Having said this, across these articles I will examine five different ways I’ve identified in which game islands are used, these being: as exotic settings; as starting locations for the players’ journey(s); as ‘hub worlds’ or ‘overworlds’; to provide ‘shipwrecked’ or ‘desert island’ gameplay scenarios; and as fortresses, bases and/or lairs for particular enemies and boss characters. Part 1 follows bellow; part 2 can be found here.

The Tropical Trope

Perhaps the most famous exponent in gaming of this classical cliché is The Secret of Monkey Island (1990) and its sequels. Set on various fictional Caribbean islands, this point-and-click masterpiece paid beautifully playful homage to the swashbuckling pirate fiction that inspired it. An exemplar of the use of setting to enhance style and narrative elements within games, Monkey Island became a benchmark for future graphic adventure titles.

Even games with fewer literary or filmic influences managed some successful use of island-based exoticism. The original Crash Bandicoot, for instance, takes place across three islands comprising a fictional Tasmanian archipelago, with each island acting as a sub-world. The choice of setting was likely established after deciding on bandicoot as the race for the PlayStation mascot, as bandicoots are endemic to Australia and Papua New Guinea. However, just as Crash bears little resemblance to a real life bandicoot, there’s not much about tropical islands that makes them particularly well suited to the platformer genre: historically, such games relied on world-hopping scenarios to provide sufficient variety across level designs, a tactic that both sequels in the Crash trilogy would adopt.

Despite this, the developers at Naughty Dog made good effect of their design choice. By vaguely theming each of the islands – the first comprising dense jungles and indigenously built wooden structures, the second river based levels and ancient stone ruins, and the third industrial complexes and a medieval castle – they managed to include both breadth of design as well as iterative development of level structures and incremental increases to difficulty. The colourful nature of the first island’s jungle levels emphasised the game’s graphical elements, which were of incredible quality for the time. What’s more, given they made the game’s antagonist a mad scientist bent on creating an army of super-animals, the setting even had narrative precedence through drawing on The Island of Doctor Moreau (1896).

Crash wasn’t the first star of a platform series to venture across exotic isles. When Mario’s original rival Donkey Kong received a revamp in 1994, developers Retro Studios decided that he and his gang would be better suited to island life than being rainforest residents. The original Donkey Kong Country is set across six different areas of ‘Donkey Kong Island’ – who are we to question the naming conventions in such a seminal title? – with each area differentiated from its fellows in terms of environment. These regions again allowed for an array of stage designs: each level is given an explicit type, some of which occur across the game – ‘jungle’, ‘cave’, ‘coral’ – and some of which are region-specific – ‘snow’, ‘factory’, ‘ship’. Most outlandish is the inclusion of the ‘Gorilla Glacier’ area, possibly beginning a design trend that would culminate in Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze (2014).

Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was actually Donkey Kong’s old plumber nemesis who was the very first platform-game mascot to visit tropical isles. After including several island themed sub-worlds in Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988) – a game famous for its innovative world-maps and overworld traversal – Nintendo decided Mario’s next adventure, Super Mario World (1990), would begin on ‘Yoshi’s Island’. A sub-world of the overworld known as ‘Dinosaur Land’, like most classic Mario opening acts it served as a subtle tutorial segment, introducing the player to the new mechanics of the Cape Feather, Spin Jump, Red Switches and of course the island’s eponymous dinosaur.

Yoshi’s Island is more notable though in providing an interesting case of developing a setting across two games. For the game’s sequel, Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island, the developers chose a completely new direction for a Mario game. Possibly because they had set themselves an impossible standard to beat with the previous game, and potentially also due to the popularity Yoshi had garnered, they decided to make the dino-pet and his natural habitat the true stars of the next game (along with a baby Mario). Correspondingly, they created a new set of core gameplay mechanics to further distance the title from classic Mario. Whilst levels from Yoshi’s Island (the sub-world) of Super Mario World had felt somewhat familiar to stages from its prequels, those of Yoshi’s Island (the game) felt totally distinct and deserving of having a game named in their honour.

The level structures, creature designs, crayon aesthetic and animation style combined to create a world that was fuzzy, friendly, yet also tinged with fright. The pastel shades and rough outlines of the visuals suggested degrees of warmth and texture in the environment like no Mario title had managed before. Like many of the previously discussed games, a variety of climates and terrains were crammed onto the island, but – in my view – the combined effect of the aesthetics lends it a greater unity, and makes it feel more like a unique virtual place rather than a mishmash of level types. It could also be viewed as a playful transformation of two old tropes – a ‘mysterious island’ and a Lost World type ecosystem – into a cute, challenging and aesthetically splendid platform title.

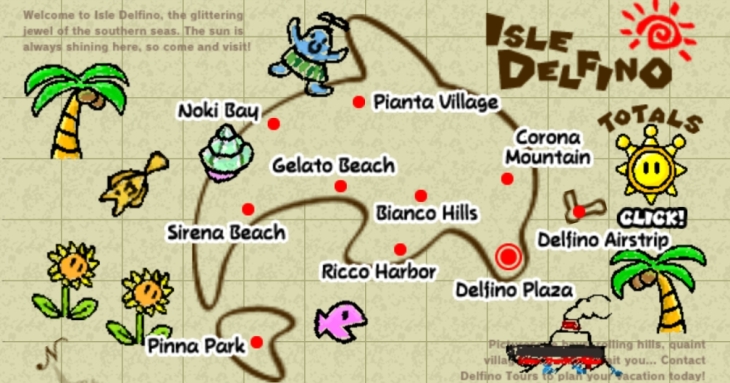

Mario’s next near-disastrous trip to a seeming island paradise came in Super Mario Sunshine (2002). The title was set on the ‘Isle Delfino’ (‘Dolphin Island’), which was implied to be a fictional Italian island (much in the same way that Mario is apparently a fictional Italian). The name was also an allusion to the original codename of the Nintendo Gamecube: it’s fun to imagine that the name ‘Project Dolphin’ partly inspired the theming of Sunshine and Zelda: Wind Waker (2002, more on that game later in the series), which – along with Wave Race: Blue Storm (2001) – made the Gamecube partly synonymous with great water-themed games.

Sunshine’s narrative begins with Mario, Peach and a few friends heading to the island for a trip, a rare example of a game beginning with its hero attempting to go on holiday (the backstory of Super Mario World establishes a similar scenario). The island acts as a pseudo-open world structure, allowing the player to access various different levels from the central hub of ‘Delfino Plaza’. Though it doesn’t necessarily integrate exceptionally well with all design elements, the island setting does serve several purposes. Firstly, it foregrounds the water-based mechanics central to the game: Mario is tasked with cleaning up a strange colourful goo that has covered parts of the island using a glorified pressure washer. Secondly, it layers the sense of exploration inherent in 3D Mario games: whilst Mario had explored many different lands before, this time he’s ostensibly a tourist! Finally, the differences in environment and terrain compared to prequel Super Mario 64 (1996) – in tandem with the aforementioned water mechanics – serve to mark Sunshine out as a very different sort of Mario game. Indeed, for many it is the black sheep of the series. The setting thus helps provide the game with a unique identity within a series that is often accused of overly familiar world designs and aesthetics.

Perhaps the game-islands most functionally similar to real-world experiences of tropical islands are the two found in the Animal Crossing series. The first, known simply as ‘Animal Island’, appeared in the original Animal Crossing (2001) and featured several elements and mechanics intended to make it feel like a vacation-type area: it can only be reached by boat; it has a large, empty bungalow for use by the player-avatar; it has coconut trees that drop their fruit, which along with beach-strewn shells can be collected; items and furniture exclusive to the island include a life ring, surfboard and ukelele; and the season, which changes in the main town, is constantly ‘summer’ on the island. The player-avatar can even get a tan, or become sunburnt if not careful!

In order to access the island the player had to connect a Gameboy Advance to their Gamecube, so even in terms of how the player accessed the island, it bore similarity to real-world holidays. That is to say, it’s a potential hassle to get there, but a welcome and pleasantly different experience from the main game once there. This sense of taking a break from the normal gameplay loop is perhaps highlighted by the fact that you can’t save whilst on the island. Animal Island’s successor, ‘Tortimer Island’ from Animal Crossing: New Leaf (2012), builds on the holiday destination style of gameplay, including mini-games masquerading as guided tours, a souvenir shop, more exotic flora, and the ability to rent a wetsuit and go diving around the island’s coastline.

Some recent AAA games have also made use of tropical islands within their world design, such as Far Cry 3 (2012) and Uncharted 4 (2016). However, as I have little direct experience or knowledge of these titles, I’ll refrain from passing comment. One particular standout example of a tropical game-island from very recent memory is ‘Eventide Island’ from the groundbreaking Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). However, as the gameplay of this island features a particular twist (spoilers!), it’ll be discussed in a later part of this series. For now, here’s hoping you’re laying on a beach reading this, with a windbreak flailing to your side and sky-rats seagulls screeching merrily above you!

One thought on “Little worlds within themselves: the use of islands as setting and structural elements within games, part 1”